“Where do you fall on the Kinsey scale?”

I immediately became flustered as I read that text. Nervous my family would notice my change in mood, I ran to my bedroom to think. This was the first time I’d been back to Texas after starting my freshman year at Caltech, where I’d met the friend who sent me the message. She was from San Francisco, so it was probably safe. My hands shaking and heart racing, I finally pressed send.

“Um…probably a 3. But I’m going to marry a guy and live a normal life.”

I’m going to marry a guy. I repeated that phrase over and over in my head trying to convince myself. It was the phrase I told myself every day up until this point.

Except for the girl I had held hands with a few days before school ended for the term, I’d never come out to anyone. I was too scared. I grew up with my best friend in the world constantly saying that gay people disgusted her and hearing extended family members compare gay relationships to bestiality.

That’s part of the reason I chose Caltech. I matriculated here in part to escape the conservatism of Texas, to do research at the top science university in the world, and to play NCAA Division III tennis.

Since I’ve been here, I’ve loved it. Most people have been supportive of who I am, and slowly I’ve learned to accept myself.

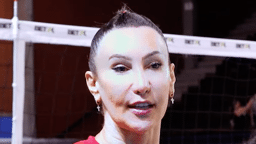

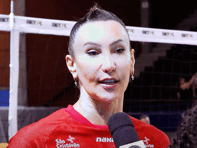

Two and a half years after the Kinsey-scale text, I’m still dating the girl whose hand I first held. She is the smartest, kindest and most beautiful person I have ever met. She encourages me to do my best in creating positive change, reminds me to be kind to everyone, and loves me for who I am.

“By fighting against institutional discrimination, we can create a world where society supports LGBTQ members.”

She graduated after my freshman year and has been living in Seattle ever since. When I picture my future, she is always in it. Now, instead of repeatedly telling myself that I will marry a man, I count the days until I can graduate early and be with her forever.

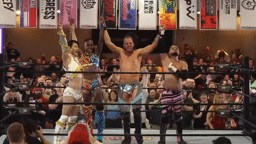

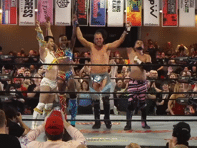

Throughout my time at Caltech, my tennis team has been incredibly supportive of my relationship. Our assistant coach at the time was the second person I came out to, then the captain, then the rest of the team. At the SCIAC Championship last year, the team wore pride shirts to our first-round match to support me.

However, wearing pride shirts to a match isn’t enough anymore. So today, I choose to come out to the world.

And I’m asking the world to take action.

A few months ago I was researching schools on our match schedule. I found out that one of the schools we were scheduled to play, East Texas Baptist University, is a Christian school that has an exemption to parts of Title IX. That exemption allow it to discriminate against the LGBTQ community while receiving federal funding.

When I saw this, I was completely appalled. How could a school accepting my tax dollars discriminate against people like me? How was this even legal?

About a month and a half before the match I presented this to my coach, who talked to the Caltech athletic department. The response was that I should speak with the Title IX Coordinator to learn how to work with people whose opinions are different from my own.

As a liberal atheist non-straight vegetarian from Plano, Texas, I already knew how to do this. Nonetheless, I met with the Title IX Coordinator anyway. Over the next month, we did our research and contacted ETBU to verify that this Title IX exemption was indeed in effect.

As the match approached, I decided to talk to my team about it. I explained to them how it made me feel to play a school that openly discriminates against people like me. How when I walk onto the tennis court, I can’t forget that these schools lobby against legislation that would protect the rights of people like me. How I can’t compartmentalize the time someone yelled “fag” at my girlfriend and me because these schools’ policies legitimize discrimination and give people a platform to hate.

When I told this to my team, complete silence followed. Then, the captain spoke up and said, “I think I can speak for the team that we want to support you and your relationship.”

As an LGBTQ athlete, this was a defining moment for me. This was the moment when I fully felt included and wanted by my team. Not only did they not mind that I’m in a same-sex relationship, but they wanted to make sure that I could have the best athletic experience possible, regardless of my sexual orientation.

In the following days, we all co-authored and signed a letter asking the athletic department to cancel the match. Despite the team’s request, the athletic department refused.

As a result, we weighed the two options we had left: Do we forfeit the match as a team, essentially taking a 9-0 loss, or does the rest of the team play while I sit out?

After much discussion, the team decided to play the match while wearing pride shirts. They didn’t want to give ETBU the satisfaction and benefits of getting an easy win over us, especially since we were ranked 40th in the nation at the time.

However, this decision was very difficult on me. When I joined the tennis team, I joined to experience the team camaraderie that comes along with competing together, not to feel socially isolated from my team members.

Yet I simply couldn’t bring myself to take the court against a school that openly discriminates against my community, so I sat out that day in Texas, waiting in the airport alone while my team finished the match.

“I simply couldn’t bring myself to take the court against a school that openly discriminates against my community.”

My teammates won the match, 5-4, in an upset.

Since the match, I’ve been working to make sure LGBTQ athletes in the future don’t have the same experience that I did. I’d eventually like to see institutions of higher education welcoming to everyone and that those schools that do have anti-LGBTQ policies do not receive federal funding.

To push these changes, I believe that schools like Caltech that value inclusiveness should institute policies of not engaging with schools that discriminate.

Taking this a step further, I think the NCAA should ban schools with discriminatory policies.

While I believe it’s important to protect the rights of religious people, and that not everyone at discriminating schools supports the policies, these arguments are irrelevant to the issue at hand: These policies harm LGBTQ students and employees.

There is a fine line between protecting peoples’ rights to practice their religion and using religion as an excuse to hurt others. Even if students don’t follow the policies at the school, it creates an environment of secrecy and fear amongst LGBTQ members that doesn’t apply equally to straight people.

If a school chooses not to change its policies, it is harming its own students by creating an environment not welcoming to everyone.

We can change this by bringing these issues to our schools, lawmakers and the NCAA. By fighting against institutional discrimination, we can create a world where society supports LGBTQ members, and more importantly, where LGBTQ members accept themselves.

Julia Reisler, 21, is a current junior at the California Institute of Technology where she is majoring in computer science as a member of the women’s tennis team. She can be reached at [email protected].