“What do you want to be for Halloween, Thomas?” my Dad chuckles from behind the camera.

“Well, I was between being a unicorn and Woody from ‘Toy Story.’ Daddy said the store doesn’t have any unicorn costumes, so I’m going to be Woody!” 5-year-old me exclaims as I continue to play with my sister’s Happy Meal Polly Pocket.

As far as home videos go, this one stands out as the most self-incriminating as kindergarten me was just falling short of packing up and going to brunch in Provincetown. I obviously had no idea I was gay at that age, but I always knew I was different.

I’m the child of two swimmers, so swimming was an obvious choice for me as a sport. Growing up, I loved the sport as it constantly challenged me to better myself each time I dove in.

An unexpected effect of swimming was its unparalleled ability to act as a cathartic release for my pent-up sexual identity. Who would’ve thought that waking up at 4:30 in the morning, burning 2,000 calories and then going straight to school would wear someone out?

Exhausting myself to suppress how I felt was an ineffective way of dealing with my problems, but I thought I had it all figured out. In hopes of extending this unhealthy business model for my one-man show of denial, collegiate athletics seemed to be a great bet in prolonging my inevitable coming out.

While I was applying to colleges, Washington and Lee University in Virginia seemed like the optimal place for masquerading as a straight boy. An extremely heteronormative school embedded in a dominating Greek culture, W&L offered me a place to “play the gay away.”

On my recruiting trip, I was impressed by the coaching staff and the teammates I met. The swimmers had a nice balance of dedication to the sport and a desire to hang out with each other outside of practice, which matched my ideal college swimming experience. The instant I left campus from my recruiting trip, I was determined to spend the next four years hiding who I was on this team.

The coaching staff guided me through a successful first season of collegiate swimming. They pushed me to be a better and much different athlete than what I was used to being, but I was still adhering to the same method of using my exhaustion to avoid my sexuality. I was satisfied with my season and I was eager to repeat the process three more times. The real challenge, however, came after my season ended.

I now had to face the reality that I wouldn’t constantly have swimming to act as a facade.

As a club swimmer, I had never really experienced a lull in my training. We would have two weeks off in the fall and again in the spring, but I never really knew life out of swimming. Transitioning to Division III athletics, I now had to face the reality that I wouldn’t constantly have swimming to act as a facade. Without daily practices, I slowly caught myself spending less time with friends and falling behind on my school work. In early March 2016, something happened that changed me forever.

A W&L student spray-painted anti-gay slurs directed at one queer upperclassmen. The school was outraged and kicked the homophobic vandal out of school, but the dismissal couldn’t take back the pain and suffering it caused the targeted student nor the fear it struck in closeted kids like me.

While I was not friends with them (the pronouns this person uses) at the time, the targeted student would later become a close friend of mine. Many community members rallied behind this student, showing great ally-ship and unwavering love for them, but this was not the case for all. Even if the students didn’t use vandalism as a medium for their rhetoric, this was enough to show queer students that these sentiments were alive in our community.

Shortly after the incident, countless voices around campus echoed similar points suggesting, “we’re so sorry for them. If only they weren’t as flamboyant, maybe this wouldn’t have happened.” Implying guilt on behalf of the queer student did nothing but minimize the responsibility of the vandal and promote a culture that dismissed the possibility of a queer-positive environment.

Mortified at the possibility of being outed or ostracized, I hatched an immediate plan of action: just keep swimming. I started practicing with two of my teammates training for Olympic Trials that spring, but I realized that swimming was no longer providing me refuge from the part of myself that scared me the most.

I was pushing myself harder and harder as the end of the semester pushed closer, but my efforts were to no avail. I then recognized that all attempts to suppress my sexuality were simply putting band aids over bullet holes. Lonely and confused, I entered that summer of 2016 scared that I would go back to school ready to come out and get confronted with hostile bigotry. How was I supposed to keep this up?

Entering my sophomore year, I realized that swimming was no longer the cause of my fatigue. Instead, I found myself exhausted trying to hide the fact I was gay. I can’t say there was any tipping point that brought me to this conclusion but rather years’ worth of lying to myself and the ones I love.

I struggled to get any sleep, came up with every excuse to avoid spending time with friends and dogged every attempt from my coach checking to see if I were OK. I had to recognize that what I was doing wasn’t healthy. That’s it, I decided: I’m going to come out.

In preparing to come out, I did what any Type A planner would do: I put together focus groups.

It may be a stretch to call them focus groups, but drunk friends that you’re taking care of make for great practice audiences. I only told one drunken student that I was gay, but it gave me a good opportunity to get my nerves out before telling the ones closest to me. Telling my teammates would be challenging, but I knew I could no longer invest in the team if I couldn’t do so as my true self.

I decided to start with two of my teammates on the women’s team. I sat them both down one by one, my hands shaking from the pressure building up inside me. Without any opening, the words “I’m gay” slipped right out of my mouth.

My eyes were closed in fear of what was to follow, only to be met by the embrace from the two of them. I exhaled with the weight of a 20-year-old secret slid off my shoulders. My two friends could not have been more supportive, stating they were just happy to see me happy. They reaffirmed their love for me, and most importantly made me start to love myself again. With my two closest friends in my corner, I decided it was time to tell the rest of my team.

I walked into my coach’s office the following Monday before dryland. She looked at me with a concerned look that I had only before witnessed from my parents. Before I even began my overly rehearsed spiel, she spoke up.

“Are you OK, Thomas? The person you’ve been at practice isn’t the same bubbly person you were last year,” she said.

In that moment, I froze. I was touched to know that she not only noticed I was struggling, but she genuinely cared about my well-being. I suddenly ditched the script I had all but scribbled on my hand. I decided to try and bury my coming out in a list of other things.

“This year has been really between academics, being a first year RA, coming out, finding time for friends and still trying to compete,” I replied.

“Coming out?” My coach inquired with puzzled expression.

“Yeah, Coach. I’m gay.”

Without hesitation, she exclaimed, “Oh well, congratulations! That’s a big step for someone to take, and I hope you’ve found comfort in yourself.”

Coming out to my coach was what gave me the strength to begin to tell others.

Hearing an adult I respected validate my experience gave me a jolt of energy that I hadn’t felt in years. Coming out to my coach was what gave me the strength to begin to tell others. One by one, I began to tell family, friends, and coworkers, all of whom embraced me for who I truly am.

With a rather uneventful coming out under my belt, a brief sense of relief passed over me: it’s all going to be smooth sailing from here. I didn’t realize that this marked the beginning of my story, rather than the end. I found a great sense of security among a close group of friends, mentors and family as I progressed throughout my college career.

Coming upon my final days as a competitive swimmer, I am thankful that I have been able to use the sport to embrace my sexuality rather than hide it. By embracing my identity as a gay man, I have been able to live a happier and healthier life surrounded by a group of people who truly love me for me.

I have seen so much growth at W&L over the past four years, and I am proud to be an openly gay athlete competing for the Generals. Groups like General’s Unity, our student LGBTQ+ organization, and 24, a student-athlete organization, help create a more positive athletic community.

The campus is changing for the better, but there is still room to grow. I hope that by sharing my story I can help others recognize that coming out takes time but is worth it in the end.

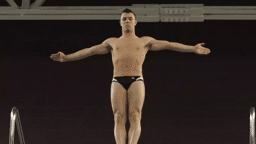

Thomas Agostini, 22, will be graduating from Washington and Lee in the spring of 2019. He is a Neuroscience Major and plans to attend medical school in the fall. He serves as the Head Community Assistant for W&L, the President of 24, and is a member of the swim team. He can be reached by email ([email protected]), Facebook, or Instagram (tjagostini).

Story editor: Jim Buzinski

If you are an out LGBTQ person in sports and want to tell your story, email Jim ([email protected]).