I just celebrated three years of marriage to my husband with whom I’ve been with for seven years and I have rowing to thank for it.

Outside of several special people in my life, my time as an athlete played the largest part in defining who I am today. It even brought me to meet my husband, who was also an athlete and fellow rower.

My time with him has brought more happiness than I ever thought I deserved and more than I could ever earn. I have a much different life than what I thought was possible for growing up without any gay influences or role models. It is decidedly different from what my family wanted for a straight son. And since I didn’t have a lot of friends growing up, I assumed that much of what was available did not apply to me because I am gay.

To this day I am still curious why it was important to announce to strangers I was gay when walking into a classroom, a locker room or a dining room. As a kid, I honestly didn’t know the reason I felt different from everyone.

Without knowing a single thing about being gay and never having met an openly gay man, I feared being gay from as long as I can remember. My experiences told me that it was bad to be gay.

Regardless of the sport I played, and how far I succeeded, I never really got the chance to enjoy any of them. Wherever I was dropped off for practice or whatever field I stepped onto, I knew I would be playing hard to win but also fighting against my own teammates.

As I got older the name calling got more hurtful, the shoving and chasing got more frequent, and I stopped playing sports all together. I hated having to stop. I hated having to lie about it. I still hate the word faggot. I never felt confident that it wasn’t me who was causing all of these problems.

I started college in the mid-1990s which coincided with the politics and publicity of the AIDS crisis. By the time I graduated college, HIV transmission had hit its height within the gay community. I didn’t know much about it, but I did know that the same names I was being called in the hallways, lockerrooms, and sports fields were showing up in newspapers across the country.

It was something on everyone’s mind, but there was never any conversation or education. And so, I never dated women or men. I hoped that by not having to choose, I could somehow fly under the radar. Still, I had never met an openly gay man or talked to anyone about HIV or AIDS. I was full of fear. I was terrified of AIDS. If I was gay, then the thought of sex translated to a death sentence.

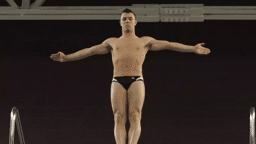

Amid all my confusion, I looked for a sport that was unfamiliar to most and would take me away from the familiar sport settings I was looking to leave behind — and so I joined the newly established rowing team at college. It didn’t hurt that the only rowers I had ever met were hunky, muscular and extremely athletic.

My rowing career took off in 1997 with my being selected at a USRowing National Identification Camp at the Princeton University Boatclub. Based on the morning erg- machine race times, I was one of 16 rowers to be selected for an afternoon row with lightweight men from around the country and be coached by the U.S. Olympic coaches.

To me, this was proof that there was nothing wrong with me. And if I was gay, I knew I could blend in and hide in my achievements. It also felt amazing to be good at something and have it be recognized and celebrated by coaches and teammates.

I will never forget stepping into a fiberglass boat for the first time and not one made from wood. I will never forget how much I struggled with my technique coming from a state school and such a novice program. I will never forget how I still felt different from everyone else.

I left college finally winning a New York state championship and left behind a few campus records. I also left college never having dated anyone. I wondered why I still never found anyone I liked or anyone I liked back

After college, I was accepted to one of the best lightweight rowing development camps in the country — Riverside Boatclub. While it was my hard work that got me accepted, I was also accepted socially and was never made to feel different or unwelcome.

We all took care of each other, looked out for one other, and supported each other in ways I thought were not for me because I was gay. Still, I never once showered with the team after practice.

My first summer we won every race we entered. This elevated our status as a club but also as individual rowers. I could now only race at the elite level. I returned to Riverside the following summer after my first year of law school.

And it was then when I first sheepishly showed up at gay night club on a random Saturday night and danced all night in the middle of the dance floor with my eyes closed. I met my first boyfriend there. Before I left the club I asked him if he had AIDS. Not knowing how to talk about it or how to ask, I was met with understanding. He had lost his boyfriend to AIDS two years prior.

That summer I tapped into a part of me that was not as angry. I finally felt a strong connection with my club, coaches, program, and sport. During the third summer at Riverside my rowing partner and I entered the U.S. National Open Trials to challenge the incumbent Princeton boats to a spot at the U.S. World Championships; it was the highest race in a non-Olympic year. Best two-out-of-three races guaranteed you a spot. We won the first two races. And in two months we were on the international racecourse in Lucerne, Switzerland representing the USA. I came back and left law school to accept an invitation the Princeton Olympic Training Center.

The stakes were higher this time. I had just come out to my family and was now entering the most competitive aspect of my life feeling the need to hide myself more than ever. We were one of eight lightweight men gunning for four Olympic seats.

Between 2000 and 2004, this was my time to make whatever impression, record, and boat needed to make an Olympic berth.

In 2001, my pair partner and I split upon returning to the U.S. He was to the begin his graduate work, and I was about to complete mine. What most people do not realize is that you cannot just put two people of equal speed and technique in a boat and expect equal results. There is a sense of magic that happens among a crew and between teammates. The variables required to match and anticipate another person in a boat, when achieved, can be spiritual. I don’t imagine a rower will ever hold a gold medal without recognizing this wholly specific feeling.

And so I grinded away at practice. Each day I tried to earn my spot and respect among the crew and coaches. I made some boats go fast, and I slowed down others. For several years I managed to hang on, but never really to excel. I think the fire inside of me grew small and what kept it burning just wasn’t working anymore.

As the next summer Olympics came into view, so did a lot of very talented rowers. A shift in the U.S. Rowing organization also arrived and the U.S. Olympic Rowing Center began to lose its relationship with Princeton University. The organization was in complete transition. Even with two Olympic lightweight men boats, there was no funding and a disproportionate amount of time spent developing these events and corresponding athletes. What many people don’t know is that we had to pay our own way to world championships through money raised by Riverside and the rest put up by my parents.

When the U.S. Olympic Training Center left Princeton University around 2003, it moved to a lake close by but the Center itself was still yet to be built. I was one of several people cycled out of the training center as they both rebuilt and prepared for 2004. I left to finish my last semester of law school and train a nearby club in New Jersey called Nereid Boatclub.

I never returned to that level of competition. I did however enjoy the training I did experience. I made boats go fast, created new bonds with teams and clubs I never dreamed of making, and am still very thankful for the rowing community for embracing my skills and experience, but also never asking me to be someone who I am not.

As a new gay man, I could not draw from the same experiences nor make the same jokes and still protect my identity.

As a new gay man, I could not draw from the same experiences nor make the same jokes and still protect my identity. I was still uncomfortable around men and was unable to break through and form bonds outside the boat club. My perception was that anything different would threaten the speed of the boat and deter being selected for the top crews. I think I stopped going fast again because I lost the courage that got me there.

I still think much of my speed and success as an athlete was motivated by anger. I really do think it gave me an edge as much as it helped me cope. Misplaced and as toxic as it was, it was where I went when I needed to dig deeper in a race and release the pressure to perform. This was unbelievably exhausting to sustain. Success without inspiration, when you have no one to share it with, darkens even the brightest of spots. I am thankful that I was able to remove myself from unsafe and unhealthy situations.

I think I could have gone further in rowing, been more successful, and been a better athlete if more people believed in me with sincere encouragement.

If I had the courage to be myself at the Olympic Training Center I still wonder if I could have made my boats go even faster. While I miss my sport every day, I do not miss feeling that I have to do anymore of this alone.

Keeping secrets and the energy I used to protect myself required an incredible amount of effort. I would like more than anything to be able to provide support and be a voice for someone else who needs to be heard and understood.

Erik Limpitlaw, 42, lives in West Hollywood with his husband Philippe Bowgen and their cat, Constance. He works for an LA-based non-profit managing licenses as part of the Statewide California Electronic Licensing Consortium (www.SCELC.org). In his spare time, he is working to launch his own creative brand to bridge the gap between the LGBTQIA community, allies, and families. (www.Exclamation-Shop.com). Erik is constantly looking for a place to coach and row. He can be reached by email ([email protected]) and Instagram (@limpitbro).

If you’re an LGBTQ person in sports looking to connect with others in the community, head over to GO! Space to meet and interact with other LGBTQ athletes, or to Equality Coaching Alliance to find other coaches, administrators and other non-athletes in sports.

Story editor: Jim Buzinski

If you are an out LGBTQ person in sports and want to tell your story, email Jim ([email protected])

Check out our archive of coming out stories.