Standing next to the trampoline at the Ariake Gymnastics Centre in Tokyo on July 31 was a moment I had envisioned in my head a million times.

I’d proudly worn the green and yellow of Australia on the international stage for 13 years, but this time was different. The moment my fingers touched the trampoline in front of me I would be an Olympian. I closed my eyes and took a deep breath — it was like electricity through my hands as they pushed me up onto the trampoline, beginning my life as an Olympian.

There were so many more magic moments like that in the few hours I was out on the competition floor. I remember standing out the back, giving all my fellow Olympians fist bumps as we smiled and said good luck to each other, a moment that was so brief but had such an emotional impact on me.

I made it out of the qualifying round and was among 16 of the top gymnasts in the world and I was their equal. I felt humbled and accepted by all the boys in that room, a feeling that was such a rarity in my competitive career.

We smiled and competed together and supported each other on the floor and no one was more or less than the next because of sexuality, religion or where we were from. We were all brought together by the power of sport and the unity the Olympics brings.

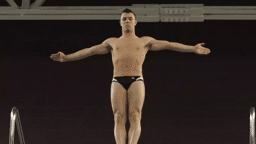

When I got onto that Olympic floor with all those other athletes, I danced and smiled, and I was campy and quirky with the whole world watching. I was composed and competed authentically and it led me to be Dominic Clarke, Olympic Finalist and Proud Gay Olympian. I was having a gay old time.

There is something special about queer athletes, an extra bit of drive and flair that lies within us, which is probably why there was such a high success rate for out LGBTQ athletes at the Games.

I knew the influential unifying power that the Olympics could have, which is why this year I publicly came out as one of two Gymnastics New South Wales’ Pride Ambassadors for the coming year in Australia.

To be able to call myself an Olympic finalist is incredible, and that is a direct result of my hard work, preparation and ability. There was more to that performance than just the reps I had done in training.

There is so much power in authenticity. It can do so much for others seeing you being authentic, but it does even more for yourself.

After not having my best competition season heading into the Games, I spent time reflecting on why that was. With some amazing advice from Ji Wallace, himself a former Olympian, I realized I was trying too hard to be the perfectly focused serious athlete and had lost that sparkle that I usually had on the trampoline. I wasn’t having fun.

Growing up, I was one of those kids who was unintentionally and unapologetically gay. Fruity and fabulous were some accurate adjectives you’d use to describe me as a child.

At home and with my family I was quiet but confident. I loved Baby Spice, complimenting women on their appearances and putting on dresses, following my sister around and putting on dance performances anywhere and everywhere.

As a walking stereotype, it was to no one’s surprise that I was a flaming human rainbow when I started coming out to people as a teen. My mum would ask open-ended “are you talking to any girls … or boys?” questions in the car every day on the way to school. This was a pretty good reflection of the support network around me. Home, training and even school were always safe places for me, and I was lucky to have that, as I know that many others in my queer family didn’t.

It’s funny to me that everyone seemed to have a clearer understanding of my sexuality than I did before I came out. Trying to figure out my queer identity at such a young age while being involved in gymnastics was confusing. When you’re a male gymnast, or involved in one of the aligning sports (like dance or figure skating), the questions begin before high school.

The questions as to why a boy would be involved in what was seen as a feminine pastime was lost on people. Before I had time to explore who I was I heard comments like, “You’re a gymnast, you must be gay” or “Isn’t that for girls?” or “You have to wear a leotard, that’s so gay.”

I spent a lot of time defending myself and my sport to protect the integrity of other male athletes I trained with, but in doing so I was lying to myself by repeatedly saying I wasn’t gay.

I remember the pit in my stomach that I would get every time someone asked me if I was gay, and the sharp pain I would feel when I lied. I’m sure most male gymnasts have encountered this stereotype growing up and this results in people in the sport creating a hypermasculine environment and culture. While I can see why lots of heterosexual boys don’t want to have an identity pushed on them that many consider taboo, the result is that it creates an underlying homophobia for many in the sport.

When I came out within my gym, I had overwhelming guilt that I was constantly perpetuating the stereotype of gymnastics by simply being myself. At the same time, I had no other queer athletes or role models to talk to or support me. It was extremely isolating.

I spent a large chunk of my teen years being severely depressed and anxious and confused as a result of this. The only openly gay sports role models I saw on Australian TV were Ji Wallace, who won silver in 2000 in the trampoline, and Matthew Mitcham, who won a diving gold in 2008. People focused on their success before their sexuality and that’s what I wanted to build for myself.

Competing at an elite level as myself fed into my beliefs about who I wanted to be as a senior gymnast. Even though I was comfortably out with certain people, I never wanted to me known as a “gay gymnast.” I wanted my gymnastics and competitive performances to speak for themselves. Because of this, I never came out publicly.

Gymnastics is such a subjective sport and the idea of “being judged before being judged” was a huge fear of mine. You never know who or what will be factors in someone giving you a good or bad score. It could be as simple as tattoos or piercings for some judges, and I thought being gay could be a negative as well.

The result was I would tone it down and butch it up in those environments. Like many other queer people, I became an excellent chameleon.

I was openly gay socially with my family and close friends. I’m lucky that as a trampoline gymnast, I have girls in my training group alongside coaches and peers that I am close to and who are nonjudgmental and accepting.

Training was fun and the biggest reason I continued gymnastics despite all my internal battles was that it was the place where my identities were harmonious and I loved every minute. I never had much interaction with most of the male gymnasts, which wasn’t a problem until I started to shine on the senior team and travel and train with the men’s team.

Being the only gay guy in a boy’s club environment is tough. The guys would try to be relatable, but after a while, the butt jokes and the constant referencing of my sexual identity started to take a toll. There were only so many times I could put up with teammates or coaches saying homophobic slurs before it started affecting my mental health.

To cope, I would let the microagressive behavior slide, keep my mouth shut and butch myself up again. This started to pull me apart from all that work I had done on embracing my identity and loving who I was. In 2016 my mental health started to deteriorate. It was isolating and embarrassing and for the first time, I wished I was back in the closet.

The turning point was in 2018. I won my first senior national championship, and I made my first World Cup final. The start of the Olympic cycle along with support from my family, friends and coaches got me back on track. I was feeling confident in my jumping and being a winner changed how I was perceived by the other male gymnasts.

It was transformative that I was finally starting to be myself and connect with all the people I’d struggled to relate to for so long, but there was a part of me that was disappointed that I only had the capacity to finally do this once I started succeeding at the highest level. It was like I could only show people my true colors once people respected who I was as an athlete.

The lead-up to the Olympics for me was the moment that I could start using my jumping for something greater than just trying to get perfect 10s.

It took a long time for me to finally tell my story and to untrain myself that identifying as a “queer gymanst” wouldn’t take away from who I am as an athlete. At the beginning of 2021 and leading up to the Games, I began to contribute publicly to the conversation about equality and inclusivity within all sport.

As an openly gay gymnast who people saw at the Olympics, I hope I can inspire others to feel pride within themself. Gymnastics is a fun sport for all ages, bodies, backgrounds and at all levels. At the end of the day, we’re just doing flips and we’re not changing the world in a major way, but that doesn’t mean that we can’t create small changes within it.

Dominic Clarke, 24, represented Australia in trampoline gymnastics at the Tokyo Olympics. Prior to the Games, he was named one of two Gymnastics New South Wales’ Pride Ambassadors for the coming year in Australia. He can be reached via email ([email protected]), Facebook and Instagram.

Story editor: Jim Buzinski

If you are an out LGBTQ person in sports and want to tell your story, email Jim ([email protected])

Check out our archive of coming out stories.

If you’re an LGBTQ person in sports looking to connect with others in the community, head over to GO! Space to meet and interact with other LGBTQ athletes, or to Equality Coaching Alliance to find other coaches, administrators and other non-athletes in sports.