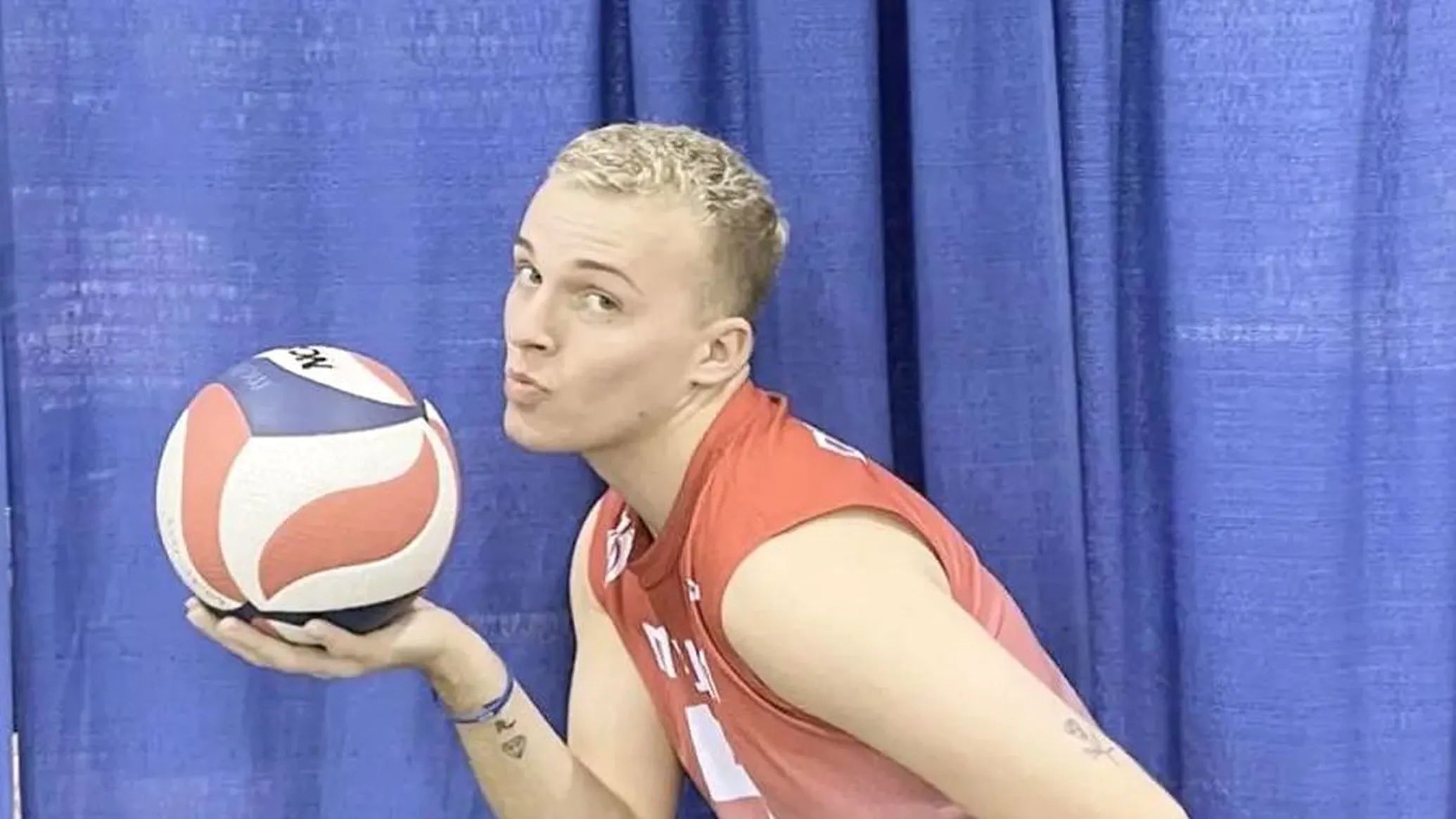

Growing up in rural Minnesota with a passion for volleyball, Connor Syverson couldn’t find an outlet for his athletic ambitions because his high school didn’t have a boys’ team.

So he made his own, practicing his skills relentlessly on his family’s farm.

“I always went home…and I passed the ball against the wall, I served against the wall,” Syverson said. “So I really put in my time by myself because my siblings were either way too old or way too young, so I never had someone to play with. I put in the effort on my own at home to really try to increase my skills.”

It was an image with a hint of Norman Rockwell Americana to it. Except for one thing.

Get off the sidelines and into the game

Our weekly newsletter is packed with everything from locker room chatter to pressing LGBTQ sports issues.

Growing up about an hour west of Minneapolis in small-town Brownton, Minn., Syverson always stood out from the crowd. By sixth grade, he knew that it was because he was gay.

“It was not a good time to be a small town gay, that’s for sure,” he said. “When I first started realizing who I was and I was different from everybody else, it was weird. I tried to fit in as best as I could but people always knew that I was gay. People could tell. I dressed different, I sounded different. It was a hard realization.”

When Syverson explored his hometown, he saw neighbors displaying yard signs that read “No Gay Marriage” or LGBTQ with a cancel sign through it. He was bullied by his peers for acting gay. With nowhere to turn for support, he internalized his feelings and tried to hide himself as best as he could.

Even when trying to divert attention with his athletic ability, he felt unsafe in some sports. During his first day of baseball practice in seventh grade, the scorching heat inspired several players to take their shirts off. In response, one of his teammates taunted, “Oh, Connor’s here. He’ll get excited, better put your shirt on.”

Feeling targeted and ashamed, Syverson walked off the diamond.

“I haven’t stepped on a baseball field since.”

Fortunately, the volleyball court was a refuge where Syverson could relax and be unencumbered. He served as a manager for the girls volleyball team at GFW High School (which he attended from 2010-14) and showed tremendous promise playing in the local rec league. To test his skills and refine his game, he’d travel extensively to attend boys volleyball camps, sometimes driving eight hours into neighboring Wisconsin to do so.

Even when Syverson began his college career at St. Cloud State in 2014, he was still enrolled in a school without a volleyball program. However, he kept expanding his knowledge of the game by becoming a student assistant coach with their women’s team and playing intramurals.

Early on in his college career, Syverson began a relationship that quickly intensified. As the year progressed, his partner declared his intention to move to California to join the Marines, and Syverson decided to follow him there. Toward the end of the 2016 school year, the two made a pact to come out to their families at the same time.

When Syverson told his family he was gay, his mother was loving and accepting right away, affirming him with the knowledge that she knew from an early age. However, his father’s reaction was a bit different.

“I think my dad always knew, too,” he ruminated, “It’s just that he always denied it because I was his oldest and I was his little baby and he was like, ‘You’re giving me grandkids.’ He thought gay people couldn’t have kids. And we still have kind of a rough relationship now but he’s definitely coming around. It was very, very rough in the beginning.”

Word quickly spread around Brownton, and Syverson lost a few more acquaintances.

“I pulled myself away too fast, I think,” he said. “I didn’t get a chance to get with people who I wanted to tell and really help them understand. I just said, ‘I’m gay! Bye!’ And so I think that was really challenging for me. It ruined connections in a way that I wasn’t ready to ruin.”

Syverson was hurt by the backlash but sought refuge in building a new life with his partner in Southern California and enrolling as a transfer student at Palomar College north of San Diego in 2018.

He also walked on to Palomar’s volleyball team and found himself competing at his school’s highest level for the first time. Shortly after joining, he found that he could be comfortable as his true self around his teammates and they would give him the acceptance he was looking for.

To protect himself, Syverson initially kept parts of his personality in check during practice. After two weeks of observing how people treated him, however, he decided to toss out a few snappy one liners to test the waters and found that his teammates quickly embraced him and his fun-loving style.

As he recalled it, Syverson didn’t even need to have an official coming out moment with the volleyball team — “I think they could tell” — but found that he could mention his partner in casual conversation without fear of being rejected or condemned. Having emerged from a conservative rural environment, the support he felt from these exchanges was exactly what he needed.

“It felt good to actually just breathe and be like, ‘I can just do what I want and feel like it’s OK,’” he recalled.

On the court, he realized that his coaches had taken a bit of a risk giving a roster spot to someone whose inexperience occasionally shone through. But as he improved, Syverson noticed that those same coaches eventually stopped worrying when he took the court and his confidence shot through the roof.

In 2019, Syverson transferred to San Diego State but soon afterward, COVID-19 forced everything to shut down. The pandemic prevented him from playing the sport he loved and once again single, he found that the cost of living in Southern California became so prohibitive that he decided to move back to Minnesota.

Once the pandemic ebbed, Syverson chose to resume his studies in 2021 at Minnesota State University Moorhead — a school where volleyball was classified as a club sport. Now knowing what he was capable of, he took on a leadership role. Halfway through the season, his teammates asked him to take on the mantle of club president and share his knowledge of the game with them.

“I have taught people some great skills and it was fun to show off that I’ve learned so much and I could expound my knowledge onto other people,” he said.

Thanks to Syverson’s leadership, enrollment in the volleyball club grew from “a solid seven people” when he started to 23 players in just two years. He was also voted MVP by his teammates over both seasons.

Following his final campaign, Syverson was offered a chance to turn pro but ultimately decided on taking a job as an assistant coach for men’s volleyball and women’s softball with MSUM. He currently works both jobs while preparing to graduate after the upcoming fall semester.

It’s been quite a journey from closeted athlete practicing against his barn wall to living his best life as an out coach for a Division II university and being an enthusiastic part of the Fargo-Moorhead LGBTQ scene.

“I’ve gotten to watch myself grow so much as an athlete by learning from other people and learning as a DIY-type of deal. I’m excited to share my knowledge [with others] and watch them grow in front of me,” he declared.

You can find Connor Syverson on Instagram @connor_wayne31 or TikTok @connor_wayne31.