I’m a liar, or at least I have been for the majority of my life. I had become such a good liar that even I believed some of the lies I had been telling myself.

I was born and raised in a Southern Baptist family in Atlanta, rich in Southern Christian culture. I started lying about my preferences around age 5, when the things I seemed to like weren’t the same things other boys liked. I was made fun of by those closest to me.

When I picked my college, I moved as far away as I could, to Montana. Unfortunately, my lies followed me and I ended up choosing methods to avoid the pain those lies caused that took me into drug and alcohol addiction.

I ended up involved with sport and fitness through a very roundabout way. For about 15 years I had been struggling with drug and alcohol addiction and used it to cover my pain and distance me from the lies I had been living my whole life. I just couldn’t find out how to get sober and healthy.

I liked who I had become on the outside — seemingly straight with a beautiful wife and a baby. On the inside, I kept sliding back into relapses because of the inner conflicts I had been so keen on hiding. I was so used to living this way, I thought it was normal.

Then, one day in the winter of 2018 as I sat in a sauna at my gym sweating out my sins from a relapse the night before in the northwest corner of Montana, a man saw my struggle. The pains of my relapse were clearly written across my face. I’m not sure what prompted him, but he suggested I take part in a triathlon.

“It’s great!” he said, “If I can be a triathlete, anyone can!” Something inside of me twitched and a soft voice said, “Not me. I’m a hungover drunk. This is who I am.”

After about 10 minutes of exhausting dialogue glorifying the sport, he left the sauna. I thought he’d never leave. But when he did and silence fell upon the scorching stones of the sauna, a fire erupted in my soul. A much louder voice took control and rattled my bones: “How long are you going to keep lying to yourself with all this, ‘This is who you are’ bull?” It continued, “Pick your head up, this is not ‘Who you are,’ this is just what you’re doing!”

In response, I decided to do something different to see what I could become. I had no idea this decision would bring me to where I am today.

Triathlon was something different. I knew nothing about it and it frightened me. This forced me to begin something I was actually quite good at: radical acceptance. Hiding had become second nature and a form of survival, ever since the day my family laughed at me because I liked Minnie Mouse’s blouse more than Mickey’s. Around this same time, I was molested by a cousin and also raped by a woman who was 20 years older than me.

Out of shame, I started to force myself to like “boy things,” like baseball and boxing gloves. But then it got really confusing when I started to have crushes on my friends. On top of confusing, it also got scary and the trauma made me generally oversensitive to all things related to sex.

This happened just as the AIDS crisis was beginning to blow up globally, adding more fear. When I asked my parents how you contracted it, they told me boys got it when they liked other boys. Also, being raised Southern Baptist, I was told that boys who like other boys don’t get to go to heaven. I was wrong in every way.

To drop my drug and alcohol identity meant I would have to accept who I was.

Out of fear and confusion and shame, I began rejecting who I was. Looking for an identity that felt right I ended up with one based on ease — drugs and alcohol. I couldn’t just stop after the party ended and consequences began to build because to drop my drug and alcohol identity meant I would have to accept who I was. But seeing that drugs and alcohol had nearly killed me through overdoses, got me four DUI’s, and led me to suicidal ideation, I really didn’t have a choice.

I was so scared. I knew that the only way for me to live sober was also to live as a gay man, yet I was willing to take this to the grave. Until the man spoke up in the sauna, “If I can be a triathlete, anyone can!” This nudged me. Maybe this was an identity I would be able to assume in sobriety while keeping myself in the closet.

What I didn’t know is that triathlon would push me so hard to accept many things about myself and each time I accepted one of these things I felt better, not worse. Triathlon began tearing down my associated fear of self-acceptance and building my confidence at the same time and these two things don’t mix well for a man who wants to stay in the closet.

The first day of training I thought I was going to die. I got out of the pool and pulled myself over the edge like a wet, crippled dog. This was going to take a lot of work. This was the first reality-based form of acceptance I had experienced in years and it was pretty obvious.

I could barely swim 100 yards without stopping and somehow I was supposed to swim a mile in my upcoming race? Madness. But, like the man in the sauna said, “If I can be a triathlete, anyone can!”

As time went on, I began realizing I was learning more about acceptance then I was about triathlon. I was learning to accept all of my weaknesses in both character and sport. I finally accepted that I had become an addict and alcoholic and this helped me to remain clean for nearly six months (prior I can’t remember a sober moment since I was 13). Then, two weeks out from my first race I found myself lying in bed, heart racing. Why? Because triathletes run in Spandex! I was going to have to wear Spandex in public? I relapsed the next day.

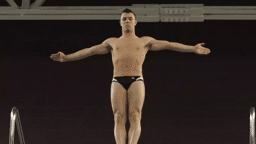

Luckily, after my relapse I woke up and continued training. On race day, I donned my Spandex and took flight. I loved it. I felt like a leaping leopard with clouds on my feet. By the end of the race I had become a proud queen sporting Spandex. But I had a long way to go. Triathletes also wore Speedos and shaved their legs. This was a leap I was not going to be able to take. But, I did.

First came the Speedo. I lost my swim jammers and had to rush to the store. I never missed a swim day. Unfortunately, a tiny little black suit was the only competitive swim gear available.

“Screw it, this isn’t going to ruin my training plan,” I said to myself. I purchased the tiny material, shoved it in my pocket and drove to the swimming pool. I accepted my fate, donned my itsy-bitsy Speedo and jumped into the pool hoping no one saw me. By the time I got out, I was in a totally different mindset.

Not only did I feel like an electric eel slipping through the water seamlessly, I also felt mad sexy and wanted to show it off. I sent a picture to my wife and received silence on the other end of the line. She always texted back.

Pride and confidence was building through my developing athleticism.

When I got home, I asked her what she thought and she laughed. I was taken back to my childhood, with feelings of shame, fear and confusion. But there was a new feeling. One of pride and confidence that was building through my developing athleticism. This allowed me to reject shame for the first time in my life. For the first time, I didn’t need to drink because of the way I felt inside.

Next came the night before the big race. I had been doing smaller races for two years, but on this day in 2019 thousands of triathletes swarmed Boulder, Colorado, for the half-Ironman. That night, a voice inside me said, “It’s time to fully accept the triathlete inside.” I had to shave my legs.

I know it may sound petty. But for me, facing this fear was shedding my masculinity. People talk about being nervous about a big race. All I was concerned about was shaving my legs. But I now had pride and over two years of training I now had confidence.

For nearly two hours I labored away and watched the last traces of my superficial masculinity slip into the drain. I emerged from the shower smooth as a lizard and I felt fabulous. My wife was going to hate this.

I stood there before the race and saw my wife’s eyes become ghostly clouds when she saw my smooth, radiant skin. She was more than let down; she was devastated. My dad laughed and my son snickered. But this time the disappointment and laughs didn’t tear me down. Those days were no more and all of the things that led me to hiding now seemed to fuel me.

The moment they saw my shaved legs and I felt a surge of power and strength from acceptance, I knew that this finish line was going to stand for much more than a declaration of endurance.

After crossing this line, I was finally going to be able to claim what I had held back for so many years. I was going to cross a new threshold and finally claim my gay.

Acceptance had worked with my weaknesses, it worked with my fears of Spandex, Speedos and smooth legs, and it had worked with my alcoholism and addictions. Now it was time to let it work for my sexuality, so that I could finally be free.

Triathlon had built up a strong body, but it also helped me to see the necessity of acceptance. At the same time, I was encouraged by everyone in the community saying, “If I can do it, anyone can.”

“If I can do it, anyone can,” was the message I heard from every rainbow I had seen during Pride week or taped to notebooks and stitched to bookbags in college. “If I can do it, anyone can” was yelled through the microphones of Elton John and Freddie Mercury. If they can, then why not me?

This, however, wasn’t easy. Owning up to my lies had some serious consequences, for myself and others. My wife and I cried endlessly over the truth. My coming out was far from rainbows and pink clouds.

Ultimately, we have begun accepting that to show our son a life of integrity we must be willing to live our truths no matter what the consequences. To show him, and others, the importance of living this way is to potentially steer one clear of the horrors I had to live through before coming to terms with who I am

I’m now living a life so free I’m absolutely baffled. I finally feel confident and complete in my own skin. I don’t have a fear overshadowing my every move, inhibiting me from facing and conquering challenges.

I can finally look people in the eye without trying to hide.

And now rather than sinking in my own soul lying to myself, “poor me, this is who I am,” I can finally stand with pride and say, “If I can do it, anyone can.”

I know that if I can finally stand firm and embrace myself, coming from addiction and childhood trauma, facing this truth after making a lifetime of decisions rooted in the lie, then anyone can.

Mark Turnipseed, 33, is a father, triathlete, coach and writer who is moving this month to Asheville, N.C. He founded Integrity Endurance Coaching, a program for sober LGBTQ people to realize their potential through health, wellness and fitness. He is also the author of a soon-to-be-published book on his journey. He can be reached at [email protected] or @markaturnip on Instagram

Story editor: Jim Buzinski

If you are an out LGBTQ person in sports and want to tell your story, email Jim ([email protected])

Check out our archive of coming out stories.

If you’re an LGBTQ person in sports looking to connect with others in the community, head over to GO! Space to meet and interact with other LGBTQ athletes, or to Equality Coaching Alliance to find other coaches, administrators and other non-athletes in sports.

If you are considering suicide, LGBTQ youth (ages 24 and younger) can reach the Trevor Project Lifeline at 1-866-488-7386. Adults can contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 24 hours a day, and it’s available to people of all ages and identities. Trans or gender-nonconforming people can reach Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860.