The recent Out In Sports study revealed widespread acceptance of LGBTQ athletes who come out to teammates in high school and college. You can find more here.

I am not a man. I don’t want to be a man and I’ve never wanted to be one. With that said, I don’t really feel like a woman either. I just feel like a person, and I think that’s OK.

I remember being in kindergarten in Rhode Island and going over to one of my friend’s houses, where we played with Barbie dolls and Polly Pockets. I knew that those toys had always been considered “girl’s toys,” but that’s why I wanted to play with them. In that moment and many others like it, I knew that I was different, and for a long time that was something I tried to hide.

I started doing gymnastics at the age of 7. I did recreational classes once a week at a local gym near my house and loved it. Not only because I could do flips and tricks and because I could spend time with my friends, but because I felt like I did not have to hide who I was. I could actually be who I wanted to be and have fun while doing it.

Eventually, I moved to a different gym and it challenged me in ways I had never been challenged before. It was at this gym where my love and passion for this sport would eventually turn into what it is today.

At the age of 9 (which is actually kind of old for gymnastics), I started competing. As the weeks progressed into months, I became better and better. My first season had ended and I was already training for the next level. Each year I moved up levels and by the time I was 11, I was making the change from compulsory, where everyone does the same routines, to optional, where you create your own routines based on certain requirements. This meant I would be training with a new group of people, who were almost all older than me.

At this point I was in middle school and knew what the word gay meant. I knew that boys were supposed to like girls and that they were supposed to ask them out and then they would be boyfriend and girlfriend. I knew that gay people were not normal and that I did not want to put myself through the trials and tribulations that being gay entailed. I simply decided that I could not possibly be gay.

However, one day I was watching the TV show “The Fosters.” One of the characters was talking to his girlfriend about having sex. They were not much older than me and I thought to myself: I do not want to do that, and then it hit me — I was gay.

It was like a big queer ah-ha moment of rainbows and unicorns and clarity. That’s why I did not feel comfortable asking a girl to be my girlfriend or why I never could relate to my older teammates when they talked about how hot some female celebrities were.

I was 12 at this time, so I don’t think I was necessarily late to the game, but I was still realizing how obvious it had been for basically my entire life. I soon started telling my small friend group from school, who were all girls. They were surprised at first, but we remained best friends and they supported me completely.

At the end of the summer, I wrote a note to my mom and step-dad telling them I was gay and left it on the coffee machine one weekend. Neither was surprised and both were super accepting.

But, when it came to the gym, being gay was something I did not want my teammates to find out.

I had become closer with all of them, but I was still one of the youngest in my group. They were all older and they were always talking about girls and other things that just made me uncomfortable. A lot of people think gymnastics is full of queer men and femininity, but that could not be further from the truth. In fact, gymnastics is a hypermasculine environment full of chest-pounding, bro-hugging and yelling (and not in the yass-mama-werk-the-house-down-boots kind of way).

Coming out as gay in this environment was scary. I was terrified that one of my teammates was going to find out and treat me differently. I had heard so many stories of kids who came out to their peers only to be put down and ridiculed. To make matters worse, I did not know of any openly gay male gymnasts at that time. I didn’t even know if someone could be good at gymnastics and be queer.

I had wished that my queerness was not so obvious to others. And eventually, it became something I could no longer hide from my teammates or my coaches. It was who I was and I shouldn’t have to keep that part of myself from anyone. Slowly, but surely, I became more open about it. There wasn’t one time where I made a big announcement about my sexuality, but I just started to be myself, and they soon caught on.

I could not be more thankful for how casual and accepting my teammates were. I remember coming into practice one day with nail polish on, and some of them thought it was a little strange, but nobody made fun of me or said anything negative. That is something I will never take for granted.

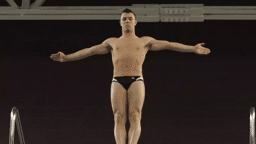

Despite their acceptance, the fear never seemed to go away. There is a certain way of doing things in men’s gymnastics. Masculinity and strong presentation are a staple part of this sport. We are supposed to be muscular and lean, and fit this stereotype of a perfect man with no fear or weakness.

I had never fit that stereotype and I never will, but I can remember always trying my best to represent it as much as I could. I knew I would always stand out, but I didn’t want people to think I was different because I was gay. Granted, I was almost 6 feet tall by the age of 14 with a big blonde Afro and the tendency to do the skills that were considered unique. I was OK with people knowing that about me, but I never wanted them to find out that I was this feminine creature who didn’t move stiffly, but one who flowed, elegantly, from here to there. Someone with strong opinions, but also someone with a lot of fear.

When I was 14, a freshman in high school, I had qualified for the national championships for the first time. I had ended up winning first place on floor and third place on vault in my age group. I was happy with my accomplishments, but I knew I could have done better. So, during my sophomore year, I had started training harder than I ever had before. This year, I had also started taking cosmetology classes, which was something I was always interested in.

That year at the national championships, I had barely missed out on placing first on vault. I was devastated with a fall on that event during the second day of competition, knocking me into second place. And when I returned home, I did not take a day off from practice. I began, again, to work harder than I ever had before.

The dedication to the sport drew out all other passions from me. And junior year, I started to hate cosmetology and I stopped taking those classes. I blamed it on just not wanting to do cosmetology any more, but I now know I hated it because it made me seem like the stereotypical gay man, the same person I had always been running from. And with that, I started to lose my connection with my queer identity.

I tore my Achilles’ tendon halfway through that year, just two days after winning the all-around competition at the second meet of our season. This threw me further away from my queer identity and my love for the sport blossomed into a massive tree. A tree that covers the ground and blocks out all the sunlight from all the other plants so they could no longer grow.

By the time I was a senior, I started to feel like a robot. Go to school, go to practice, go to sleep so I can wake up and do it all again the next day. My sense of self was completely based on my gymnastics. If I had a bad practice, then I was a bad person. I was a gymnast first and a person second.

Don’t get me wrong, I was gay, and everyone could tell. I was proud to be gay, but I also made sure I was never too gay. I was playing one of those “masculine” gay guys, who didn’t appear overly feminine. As many of my straight friends said, I was a “chill gay guy.” I look back on that year and I don’t even know who that person is.

Then came Covid-19. My senior season of high school was stripped away from me and all my hard work was just a complete waste. Or at least, that is what it felt like. I still had this black and white view of my life; everything was to benefit my gymnastics and nothing else.

The switching point was the explosion of the Black Lives Matter Movement. I can remember doing a lot of learning during this time about the history of the LGBTQ+ community and how queer people of color have always been the backbone of our community.

Queer representation became something I started to recognize more and more. I was about to be one of the only openly gay men’s collegiate gymnasts when I enrolled at Arizona State, so how could I not think about that?

I wanted to represent the LGBTQ+ community in men’s college gymnastics. But I couldn’t do that if I wasn’t celebrating queerness in all of its forms or if I hated that part of myself. In the four years of high school, I went from wearing makeup to school every day, always having my nails painted, and wearing the most creative outfits I could put together because I thought it was fun, to only wearing athletic clothes because I thought it made me look more masculine. It’s not that I had stopped liking that stuff, it’s that I started to hate the person it made me look like.

When I came to Arizona State, I began to discover a newfound connection with my queer self. It did not take away the fear or the nerves of meeting my new teammates for the first time, but it added a sense of self-confidence that a year ago, I would have lacked. I did not know how my teammates would react to my flamboyant personality, but I knew that that was who I was and there was no reason to hide it.

I must have won the gay lottery because the amount of support and acceptance I have been gifted with throughout my life is unreal. The ASU men’s gymnastics team is a family and when I moved here, I became part of that family, full queerness and all.

It’s here in Arizona where I started to embrace myself for who I was, and I thought I knew who that person was. I thought I was a gay man. But I started to feel uncomfortable and lost in that label.

One day, we were standing in our team lineup and our coach was talking and he said something about putting full effort into a task and being a man about it. It was at that moment that I knew I did not want to be a man.

In my mind, I replayed events in my life where I was put in the category of man or boy and the discomfort that came along with it. It was strange because I knew I did not want to be a man, but I couldn’t tell if I wanted to be a woman. After a couple of weeks of self-discovery and talking with one of my close friends, I finally figured out that I just did not feel like either. There are parts of me that are masculine and there are parts of me that are feminine, but that does not mean I have to identify with one of those binaries. Therefore, I identify as nonbinary.

This realization was not a turning point in my life, but it was more of a positive side effect of me reconnecting with my queerness. Gymnastics had always been the defining factor of who I was. For years, I had believed that to be my truth. And with that belief gymnastics, the thing I loved the most, stole away my queer identity.

Slowly, but surely, gymnastics became less of who I am, and more of a way for me to express myself. Gymnastics is the vessel in which I can really show my true self. I am definitely still a work in progress, but I no longer use this sport as a way to show my self-worth, by trying to fit into a box that I am not meant to be in. I can be queer and I can be a gymnast and those things are allowed to go together.

I’m still finding myself as a person and as an athlete, but I’m enjoying this journey of self-discovery and I’m not limiting myself whatsoever. I’m letting myself do things that make me feel good and comfortable, in and outside of the gym. My gymnastics has changed to represent who I am as a person and I love it.

There is still a lot of work to do for LGBTQ+ gymnasts. Our sport, like most others, is put into a strict binary, where each side is essentially is a different sport. It is difficult sometimes knowing that I will always be considered a man because I’m on a men’s gymnastics team doing men’s gymnastics.

I think the most important thing we can start doing is acknowledging the queer people in our sport, especially the ones like me who aren’t really a man or woman — they are just a person.

Jackson Harrison, 19, is a sophomore on the Arizona State men’s gymnastics team majoring in Sports Science and Performance Programming. Jackson also coaches competitive girl’s gymnastics at Aspire Kids Sports Center. They plan on continuing to coach gymnastics and continue to promote acceptance and equality within the sport of gymnastics. They can be reached by email ([email protected]), on Instagram (@jack.son.h), or on Twitter (@jacksonharrisno).

Story editor: Jim Buzinski

If you are an out LGBTQ person in sports and want to tell your story, email Jim ([email protected])

Check out our archive of coming out stories.

If you’re an LGBTQ person in sports looking to connect with others in the community, head over to GO! Space to meet and interact with other LGBTQ athletes, or to Equality Coaching Alliance to find other coaches, administrators and other non-athletes in sports.